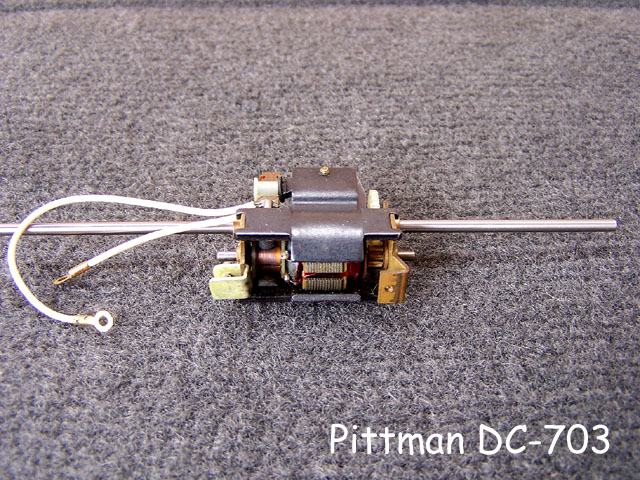

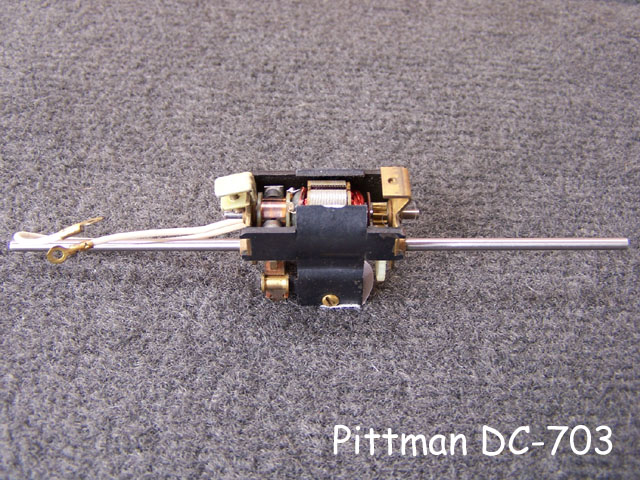

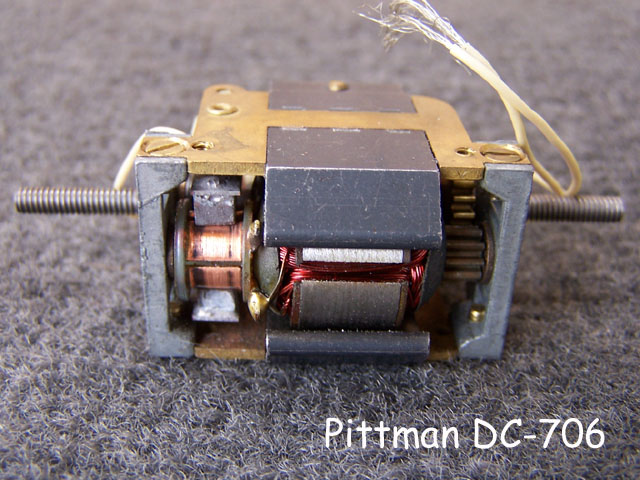

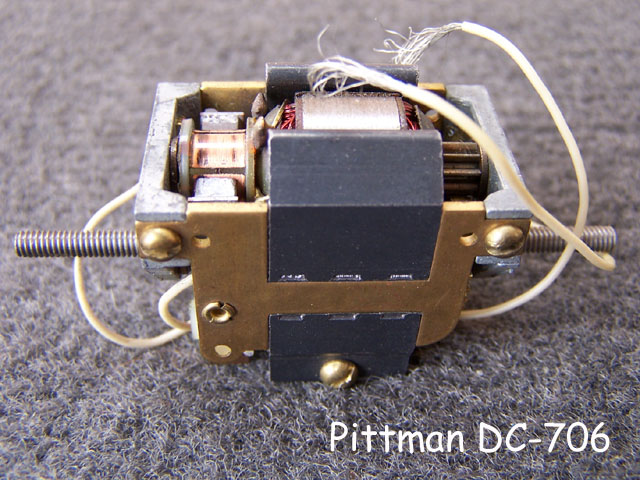

Pittman DC-703, 704, 704A, 705 & 706

Motor photos by Bob Steere, from his collection

Additional information and scans courtesy Don Siegel

Pittman's DC-700 series began with the DC-703 train motor, introduced sometime in the late 1950s or very early 1960s. The DC-703 had a very long plain (un-threaded) output shaft, and mounting brackets, used to mount the motor inside a model train locomotive:

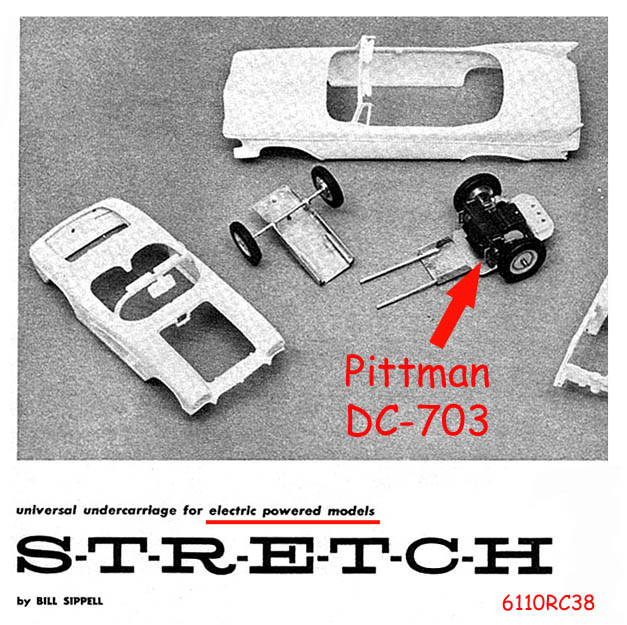

By the middle of 1961 the DC-703 was being adapted for use as a slot car motor:

To make this motor unusable for any sort of conventional slot car, you would have to cut the output shaft down equally on both sides to just under 3" total length so it will serve as an axle, or replace it entirely with a standard slot car axle. Because the stock white nylon spur gear supplied with the motor was not suitable for the rigors of racing, it was common to replace both the long output shaft and gear entirely.

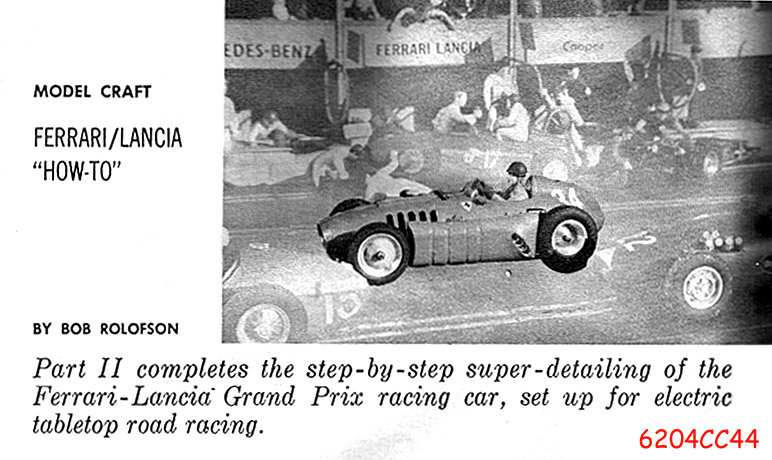

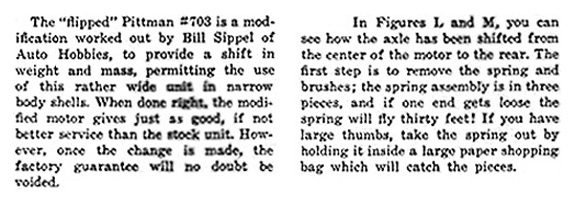

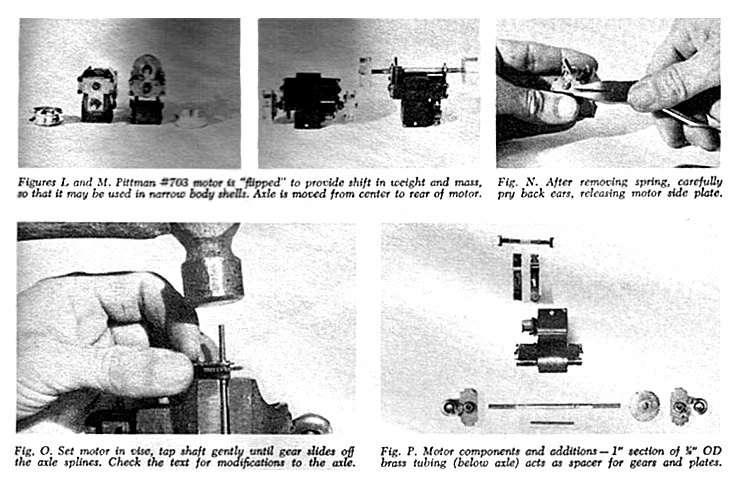

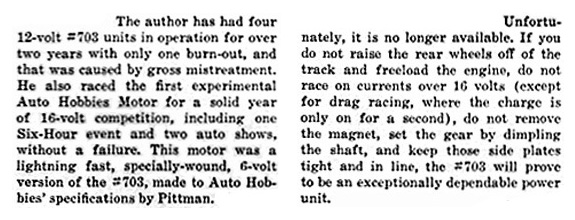

In addition, by this time the best builders began to re-arrange the axle brackets so as to place the entire mass of the motor ahead of the rear axle, instead of having it in the middle, between the armature and the magnet, which unavoidably placed some of the weight aft of the rear axle. Here’s a portion of a construction article from the April, 1962 issue of Car Craft describing the DC-703 and the process of modifying it for slot car use:

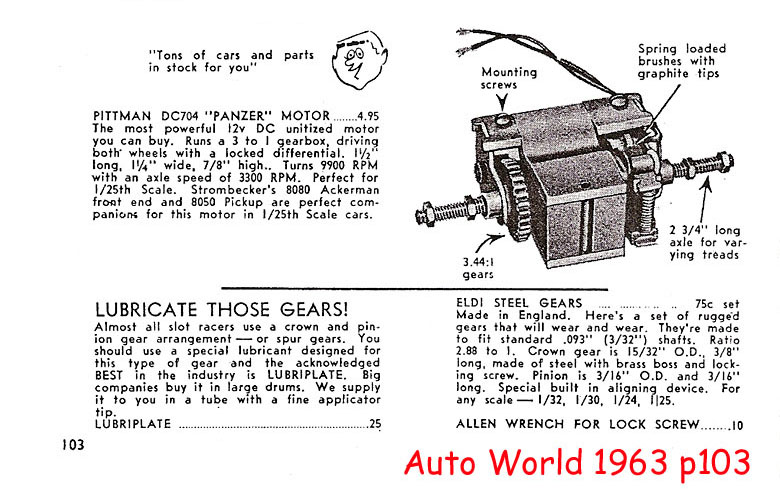

By the end of 1962, Pittman was addressing the issue of the long output shaft and wimpy nylon spur gear by introducing the DC-704, a slot car motor, which had an output shaft consisting of a 2-3/4” threaded axle, and a brass spur gear.

Pittman actually called these motors "Motor & Axle Units", because the geared output shaft extended out both sides of the motor was intended to be used as the rear axle of the car. But, the DC-704 still had train motor windings, and its output shaft (axle) was still in the middle of the motor, a situation most racers did not want.

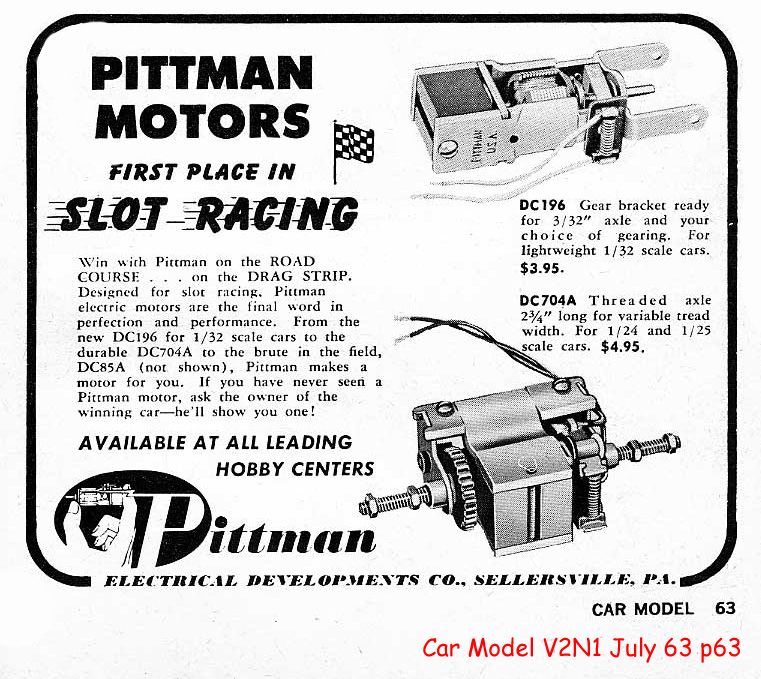

By the middle of 1963 Pittman had upgraded the train motor windings to make the unit a bit more powerful, thus more suitable for slot car use, calling it the DC-704A.

Note in the ad above the new DC-196. The paradigm was about to shift.

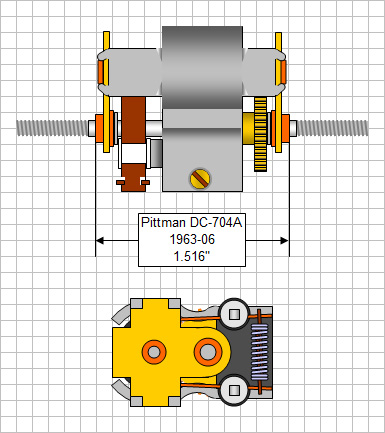

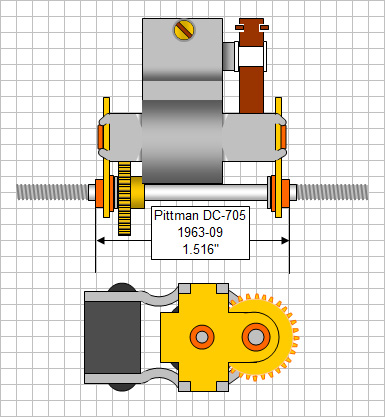

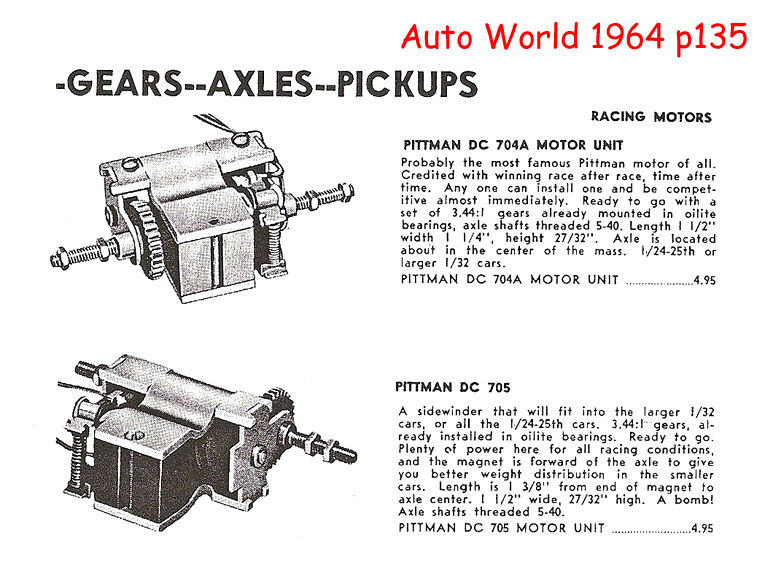

A few months later, toward the end of 1963 Pittman also introduced a reconfigured version, which they called the DC-705. The reconfiguration placed the entire mass of the motor ahead of the rear axle, something builders had been doing for a year and a half already.

Here are two drawings to illustrate how the motors were mechanically different:

Here is the specification sheet to show the two motors are electrically identical:

The DC-704A and DC-705 were sold side by side at the beginning of 1964:

At this point Pittman’s sidewinder motors were successful enough to have inspired at least two other competing motor manufacturers to replicate their basic design. The RAM DC-426 is very similar to the Pittman DC-704A, and the 426A version is very similar to the Pittman DC-705. Strombecker also offered a motor, the Devastator, which was a near exact copy of the DC-705.

Early 1964 was the high tide for Pittman’s Motor & Axle Units. But chassis and motor design was about to take another turn; remember the DC-196 mentioned above?

Improved though these two Pittman products may have been the sidewinder configuration itself was already losing supporters among the better builders and drivers.

Howie Ursaner writes: I loved these 704 etc. motors in the early days. I remember a particular orange and white scarab that I raced. The 196 was around but no one used them. There were guys running DC-70's and Kemtrons in those early days. One day I thought I would try building a super light car with a DC-196 and never looked back. This was the end for all other Pittman motors in slot racing. Nothing could touch the 196 and when we put the armature from the DC-65x in it was unbeatable until the Mabuchi rewinds eventually took over.

In what may have been an attempt to stay ahead of the competition, Pittman once again improved the mechanical design and upgraded the horsepower.

The DC-706 was the last iteration of the series, and by far the fastest and most powerful. The maximum allowable intermittent current was up 50% from the DC-704A at a full amp, and the axle RPM under load was up 12% from the 704A at 4,700. In addition, the mechanical features of the 704A and 705 had been combined so that the motor could be configured either way with a small screwdriver.

But it was like improving Route 66 after the Interstate Highway had come through.