1237-Series Design Concept, Part 2; Front Axle Rails:

Front axle rails (FAR’s) are quite simply separate rails upon which to mount the front axle uprights and front axle, as opposed to having the front axle assembly as a superstructural extension of the main rails. Certainly not a new idea, the premise is to minimize any forces working on the front wheels from the rest of the chassis.

Prelude; Front Axle Mounting:

For solid, straight front axles I have been using front and rear superstructural spanning front axle uprights since… well… the first ones I built were in late ‘68 - early ‘69, not long before the last of the “local” slot car raceways closed in MD, ending my “young” slot car geek phase until my “old” slot car geek phase began in 1995 FL. The front axle spanning uprights had a few advantages I liked: as chassis superstructure there was no need to incorporate a bend in any of the main rail wires as front axle uprights (or, to a lesser degree, add uprights as separate wires between spaced main rail wires); rather than the axle or axle tube being soldered in only at the axle uprights’ points of contact, the axle was soldered in along the entire width of the spanner, eliminating any need to tie-wire the axle to the uprights. Additionally, the front axle, and even the spanning uprights, were relatively easy to remove / reposition / replace.

Not surprisingly, some thirty-five-plus years later when I went back to scratchbuilding chassis, for those chassis that had (or had to have) straight front axles I went right back to using front and rear superstructural spanning front axle uprights for all those same reasons. Another reason would be how they easily facilitated the incorporation of FAR’s into chassis.

Front axle spanning uprights

FAR’s, History:

The three important points of track contact for any slot car chassis are the two rear tires and the guide. For all intents and purposes, the front tires are along for the ride, and in many slot car classes are eliminated. This is not an option in the “retro” scratchbuilt chassis classes. Early “no rules” 12XX all-wire framed chassis had front wheels that were largely for aesthetics, no more touching the track surface than the front corners of the chassis, if at all. This could not be the case for the retro builds, where chassis front clearance and the front wheels contacting the track surface are mandated.

I would quickly find that the relatively larger retro fronts (even trued, as they always were) could send varying degrees of unwanted vibration into an all-wire chassis frame. Whether caused by the track surface, handling stresses, or the front wheels themselves, the cause was of little matter. What mattered was the all-wire frame would just exacerbate this negative effect; as an analogy, think of a Slinky attached to a vibrator.

I knew that incorporating strategically placed brass rod / plate / sheet into a mostly steel wire frame will help to lessen vibration (harmonic) effects; we did it Back-In-The-Day, albeit with 1/16” diameter rod/wire. More recently I’d been doing it with the steel/brass “13XX” chassis. In the 1219-Series there were “sister” chassis in the “13XX” steel / brass and the steel-only “12XX” frames, using the same design to see the relative effects and chassis characteristics better. With the “12XX” chassis the goal was to make all steel wire frames so brass was not an option, especially as the diameter of the steel wire being used was smaller; even if there was 0.032” diameter brass wire, the differential between the steel and brass properties under the heat of soldering, particularly expansion / contraction, becomes relatively greater, making the chassis build problematic, often resulting in varying degrees of warpage in the chassis component structure.

The other Back-In-The-Day trick was to build an “iso-fulcrum” chassis, which for an all steel wire frame was a potential solution. (I’ll forego any repetition of the history of iso-fulcrum chassis designs, and the subsequent evolution of indie fronts that are not an option with the retro required front axle). As a matter of design and structure, the iso-fulcrum chassis would have a separate motor/drive-to-guide assembly (“drop arm” effectively) with a hinged attachment to the remaining structure(s) including the front axle supports and side pans. A few of my fellow slot car cronies of the way-back-time (and no doubt elsewhere as well) began to build modified versions of iso-fulcrum chassis, where the side pan structure was an extension of the motor/drive-to-guide assembly, and the only thing on the “iso-fulcrum” component was the front axle/wheel support structure; as a matter of differentiation in our local parlance we called them “front axle rails”. As mentioned in the prelude, the local raceways would close by the following year, and that was that for then for us…

Not surprisingly all those years later I would gravitate back to the front axle rail design concept. The only difference was they would not be hinged components, since I was moving away from the use of any hinges in my early 12XX all-wire chassis designs.

The first FAR equipped CMF3 “retro” chassis was the steel wire / brass sheet 1310-C, sister chassis to the steel wire 1225. Also, the 1310-C was the same chassis design/dimensions as the previous 1309-C, with the exception of FAR’s being added to the 1310. With track tests of the 1310-C the improvement over the 1309-C was noticeably evident, and quantifiable. The all-wire 1225-C with FAR’s was built immediately after. All subsequent 1219-Series chassis would incorporate FAR’s. For the 1219-Series all FAR’s were structural extensions of the rear motor-drive portion of the chassis, and were medial to the main rails (with the exception of the 1226, but that’s another story).

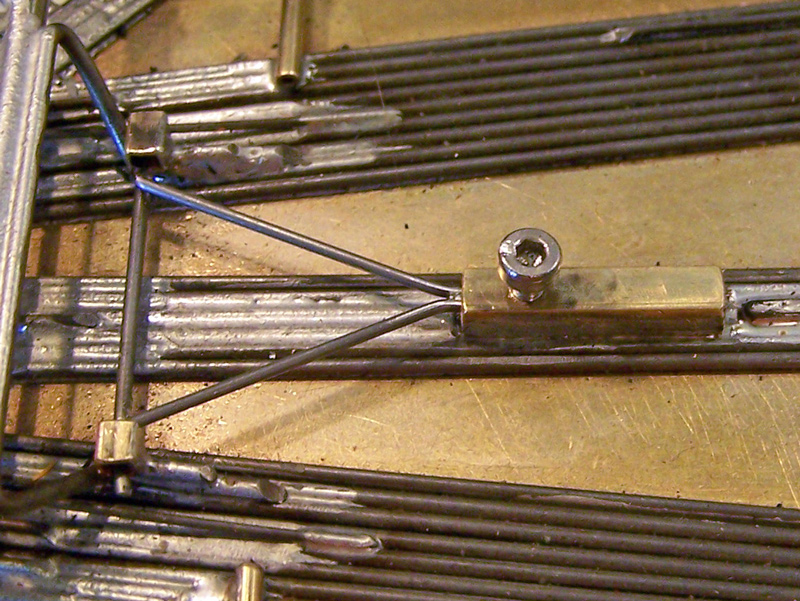

To optimize performance iso-fulcrum and FAR movement needs be restricted and moderated. Directionally, FAR’s should not move laterally, nor should they move below the plane of the chassis. They should move upward, vertically only. Early on with the 1310’s it was found this limited FAR movement needed to be moderated for proper tuning. FAR moderation was accomplished by adding a spring wire to the FAR’s. Initially the 1310-C and 1225-C had a “Y” shaped spring wire attached/soldered to the center of the chassis. It was subsequently found that regulating the tension of this spring wire was critical, but hard to duplicate with just soldering the wire in place.

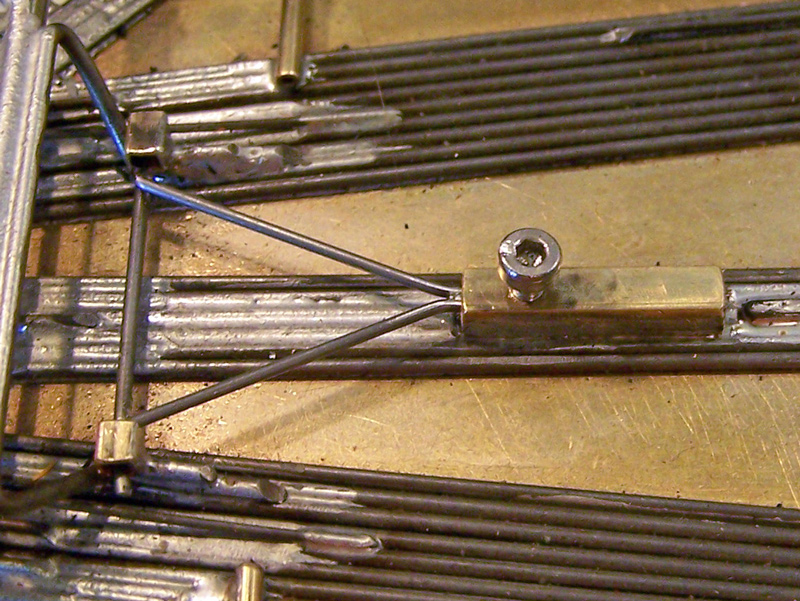

Retrofitted on the 1310-C and 1225-C, using a square brass tube “box” with a screw tapped into it, soldered to the chassis center, and extending the “Y” spring from the inside of the box to resting connections upon the front axle uprights (atop the FAR’s), a variable spring wire (VSW) system was created that could be used to better control the FAR spring wire tension. All subsequent 1219-Series chassis would incorporate FAR’s with a VSW.

1310-C; “Y” VSW

FAR Design, 1237-Series:

Intentionally, the original 1237 design/build did not have FAR’s; this was done to better assess the basic frame design and build. If the 1237 proved viable, FAR’s would be added with subsequent design/builds.

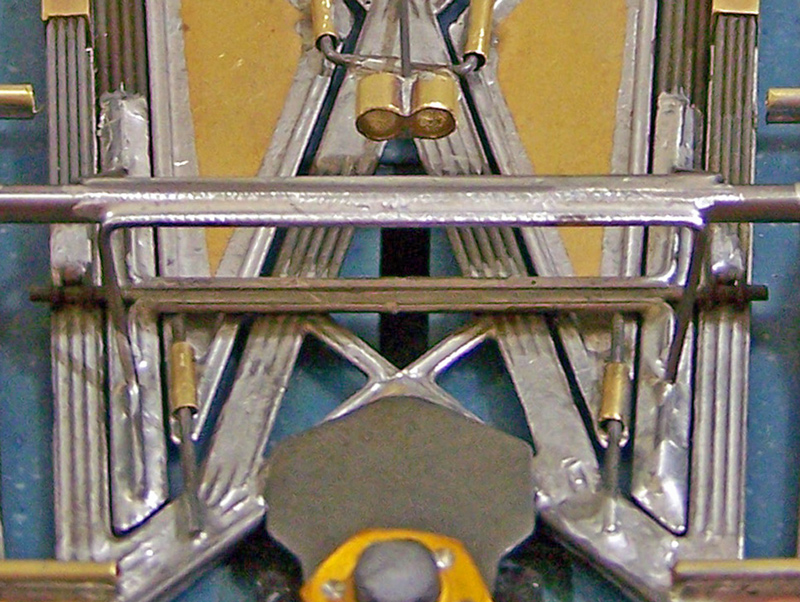

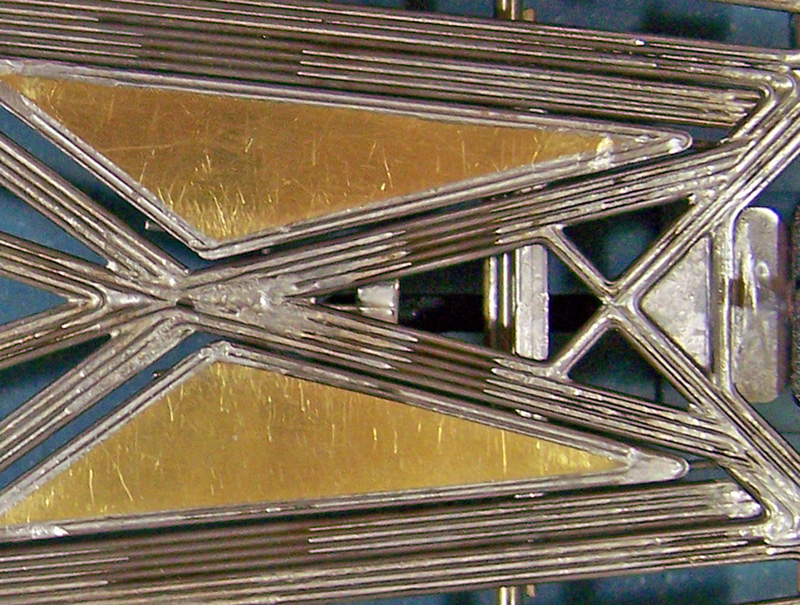

The 1239 was the first chassis in the 1237-Series to have the FAR’’s. Initial incorporation was to run dual FAR’s flanking medially and laterally adjacent to the buttress rails. The dual FAR’s were soldered to the buttress rails at their rear, adjacent to the buttress articulation. The single “Y” shaped variable spring wire (VSW) set-up of the 1219-Series was abandoned; the 1237-Series would use separate VSW’s per side for each FAR to achieve better left-right control/balance. A VSW box was soldered atop each buttress rail, with the straight VSW extending to a cross member joining the FAR pair at a point below the front axle. On the 1239 and the 1240 the left and right side FAR’s worked independently of each other. A lot of subsequent testing, designing, and mock-ups would lead to some changes to this initial layout of the FAR’s for the 1237-Series.

1239-Cc3; FAR’s (two per side) & indie VSW’s

The “2” designated FAR’s:

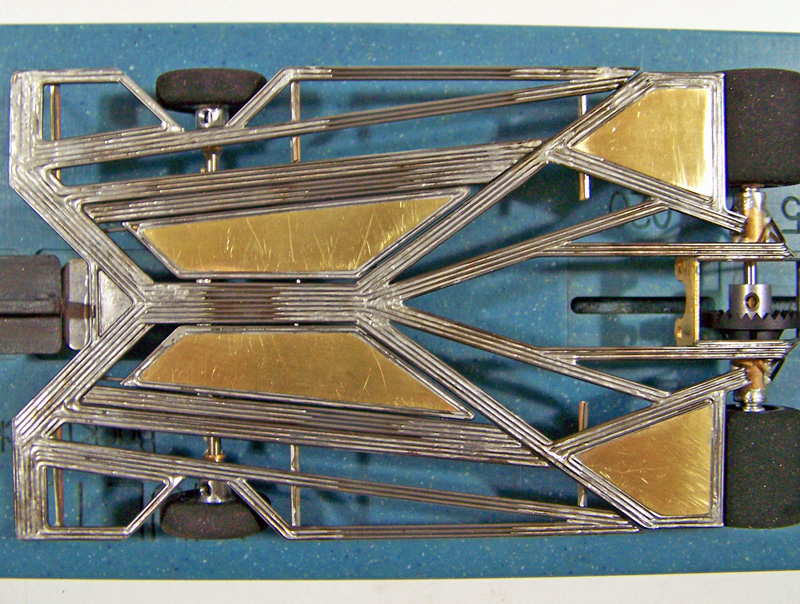

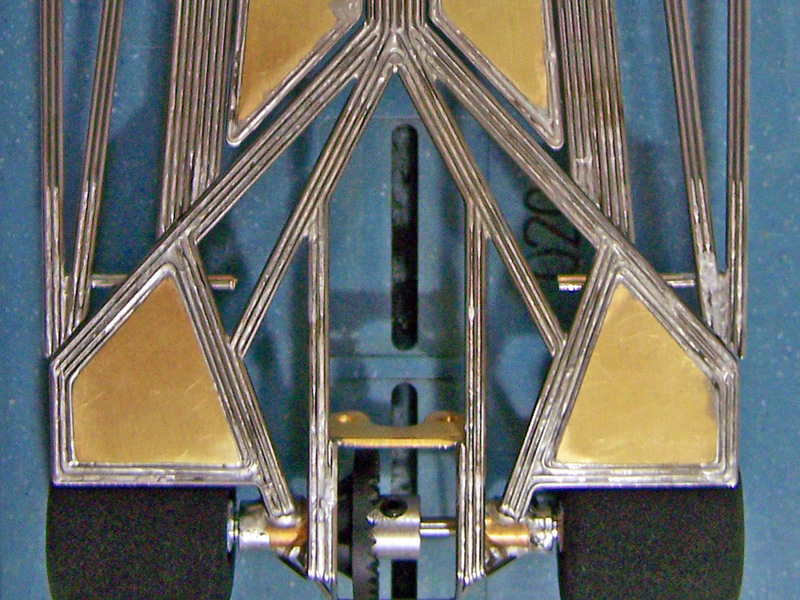

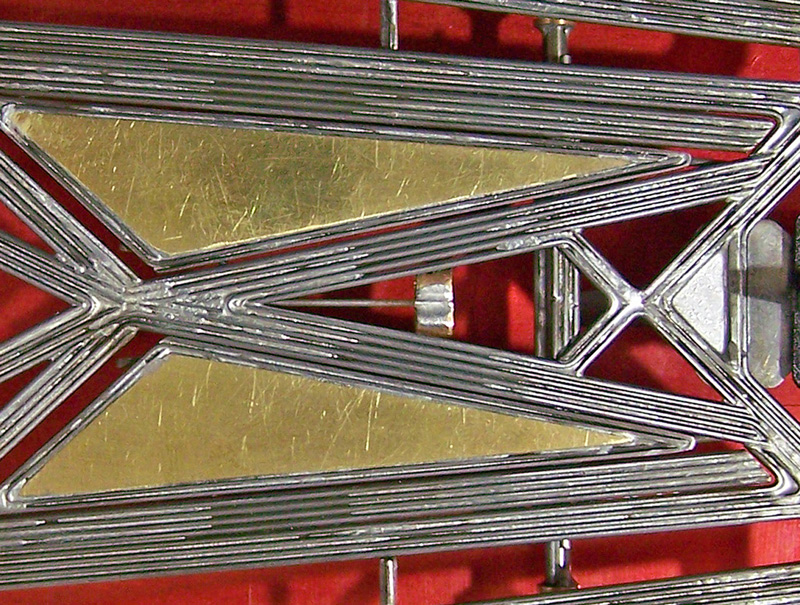

The design and layout of the FAR’s was modified and simplified with the 1241. Each FAR was now a single 4x 0.032” wire rail located medial to the buttress rail, but still attached to the rear of the buttress rails. On the previous 1237-Series chassis the FAR’s were independent; on the 1241 a torsion bar was added between the FAR’s, located below the front axle; the VSW’s extended to lay atop the torsion bar extension that was atop the buttress rails. In this way the buttress rails were still able to restrict lateral movement of the FAR’s directly (buttress rail on same side FAR) and indirectly (buttress rail on opposite side FAR). This set-up required less overall mass, smoothed out the chassis dynamics further, and greatly improved overall handling and performance.

1241-Cb3; FAR’s (one per side) & indie VSW’s (with Torsion Bar, not visible under front axle)

Subsequent FAR design variations, to date:

The “3” designated FAR’s:

The 1250 is a 1241 design with a FAR variation. On the 1250 the FAR’s, still medial to the buttress rails, are not attached to the buttress rails; they are attached to the chassis center via a 3x wire rail; they are also attached indirectly (with 2x 0.024” wires) from the FAR rear to the forward edge on the rear motor/drive assembly. The “3” / 1250-style FAR’s displayed more stable characteristics when running the chassis in high-speed / high-stress turns (and would be incorporated onto “outside” / right-side of LTO / oval racing asymmetric Stock Car chassis.)

1250-Cc3 FAR’s

1244-D3o asymmetric FAR’s

The “4” designated FAR’s:

The 1251 is another 1241 design with another FAR variation. On the 1251 the FAR’s are “quadrangular rails” that have no direct attachment to the chassis frame, having only 2x 0.024” indirect attachments from the rear of the FAR to the forward edge on the rear motor/drive assembly. This yielded smoother handling, but not enough improvement in overall performance to warrant the increased complexity of build.

1251-Cc3 FAR’s

The “5” designated FAR’s:

The 1258.5-Cb3 has a hybrid of the “2” and “4” FAR’s. The FAR is the same 4x 0.032” wire rail as on the 1241, or “2” FAR’s, but it is not attached to the rear of the buttress rail, instead being indirectly attached as on the 1251, or “4” FAR’s, with 2x 0.024” wires to the forward edge on the rear motor/drive assembly. This 1258.5-Cb3 is still under study.

1258.5-Cb3 FAR’s

There are other FAR design variations that have not yet been investigated.

FAR Location:

The relative medial to lateral placement of the FAR’s in the 1237-Series chassis frames are inherently dependent on the location of the buttress rails. While experimental mock-up testing used for spring wire location indicated there may be an advantage to having the FAR’s located medially as opposed to laterally, there are limits to this observation when applied in actual chassis construction.

This subject of buttress rail and relative FAR location in the 1237-Series is still under study.

Spring Wire Location Relative to FAR:

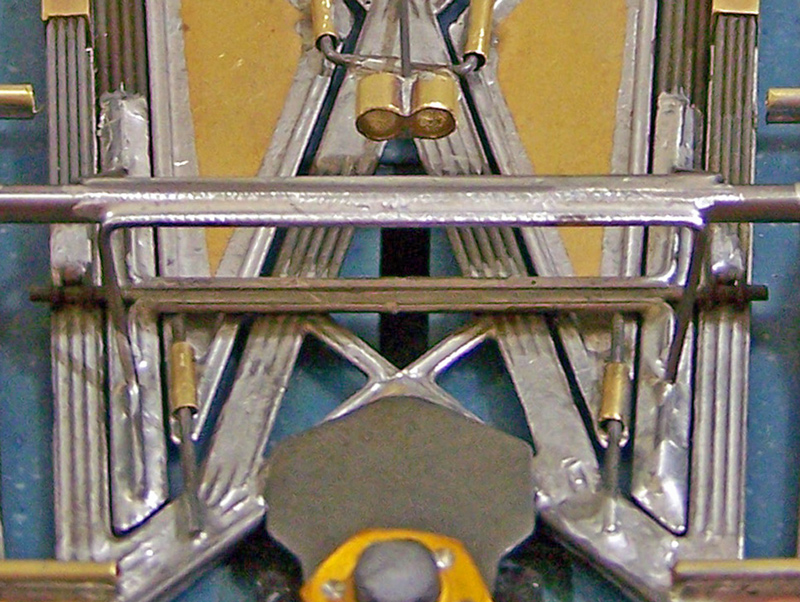

Prior to the 1241-Cc3 build some experimentation of design concepts was performed, using older 1219-Series chassis and some mock-ups. This was conducted in conjunction with the possible application of a torsion bar between the FAR’s.

Where the spring wire was located medial relative to the FAR there was an inherent increase in the amount of rotational “twist” between the two FAR’s around the chassis central axis. Moving the spring wires to a position lateral with respect to the FAR’s decreased this effect. The incorporation of a torsion bar (T-Bar) between the two FAR’s was found to decrease this effect even further, where the FAR’s worked more in unison with each other as a greater force was applied to one to mimic cornering (and possibly where one FAR acts as a dampener to the FAR on the other side, though this remains hypothetical).

1254.2-Cc3; T-Bar (view 1)

1255.2-Cc3. T-Bar (view 2)

FAR Spring Tension:

FAR spring wire tensions, from minimum (no tension other than that of the FAR itself) to maximum (or lock), and their adjustment is an area still under investigation. There have been a lot of observations to date.

The distance from the front of the VSW box to the torsion bar extension / front axle center line for the 1237-Series has been 0.875”. This number was arrived at by locking individual and sets of 0.039”, 0.032”, and 0.024” wires in a vise, then observing and measuring their deflection with force applied at different points. A WAG, basically, but one I could at least see.

Originally 1237-Series chassis with FAR’s, the 1239-Cc3 and 1240-Cc3, used spring wires that were 3x 0.032”. The 1241-Cc3 was built with a set of 3x 0.032” spring wires and a set of (softer) 4x 0.024” spring wires. The 1241-Cc3 using the 0.024” spring wires exhibited better performance. Changing the 1239 and 1240 to 0.024” spring wires improved their performance as well. Another set of 5x 0.020” spring wires were made for the 1241-Cc3 but no improvement versus the 0.024” spring wires could be noted.

On the 1237-Series Stock Car class chassis for LTO oval racing, the 1241-D3o initially, and 1244-D3o subsequently, it was found to have better performance with different spring wires on the inside/left (4x 0.024”, softer) and outside/right sides (3x 0.032”, harder).

All this has led to the fairly safe assumption that optimal spring wire tension(s) being applied to the FAR’s will most likely vary from track to track, and more than likely from one chassis style design/build to another. Since I am working within the confines of the 1237-Series designs / builds at least the latter factor appears thus far to be largely mitigated.

However, there is an observable range of limits to the spring wires having either too much tension (too “hard”) or too little tension (too “soft”), not unlike adjusting suspension springs; respectively, test observations have shown this can cause chassis to “understeer” (or “push”, the car / guide wanting to drive out of a corner), or “oversteer” (or “loose”, the car / rear drive wanting to swing out of a corner). An accurate and repeatable measuring system for VSW tension in the chassis is still in the development phase (in other words, I’m still not happy with methods tried to this point).

Some might think that having the front wheels fully removed from contact with the track where the chassis front wings make contact would be the optimal for chassis handling, but at least within the confines of “retro” rules class racing as it exists this has been found not to be the case as noted in the previous paragraph. Observably on the 1237-Series chassis any time track rubber appears on the chassis front wings there is a corresponding decrease in performance relative to the amount of build-up within the number of laps run (more build-up in fewer laps equals greater decrease in performance). While a little build-up may be acceptable within the course of the number of laps typical of a race heat, particularly on a heavily “rubbered-in” track where it can expected, typically any more than a small build-up on the front wings that can be easily wiped away with a swipe of a finger is not desirable. When “excessive” build-up is observed the FAR spring wire(s) needs to be adjusted for greater tension. While this runs counterintuitive to our collective “slot car knowledge”, it is nonetheless observable and verifiable.

FAR’s, Summation:

While the use of FAR’s on various chassis designs and builds may not be to any advantage, and may even in some cases either be an unwarranted complication or even detrimental, for fully steel wire frames constructed using small diameter wire, to date in my designs and builds from 0.047” to 0.032” wire, the incorporation of FAR’s ranges respectively from advantageous to virtually necessary.

Got all that? Yeah, me neither. What a bunch of malarkey (this sentence to be spoken in your best Bugs Bunny voice, though Daffy Duck will also suffice…).

Your results may vary. Just be sure it’s fun getting to those results.

Rick / CMF3